Many of us are helping businesses that are facing hard times, or we’re facing hard times ourselves. If you’re working for a company (or client) that’s in trouble, the use of SMS chatbots could be a way for you to look outside your normal list of solutions and help them succeed in a completely different way. If you’re a marketer looking for work, adding this to your list of skills could mean you keep things ticking along while many of the usual doors are closed — or that you open new doors.

What you’ll get

In this post, I give you instructions and code to produce not just one, but a series of text-based chatbots that can be managed by Google Sheets.

The example here is set up to work with restaurants, but could be adapted to work with any business that needs to receive orders, check them against inventory/menus, and note them down to be fulfilled.

Once the system is set up, there will be no coding necessary to create a new SMS-based chatbot for a new business. Plus, that business will be able to manage key details (like incoming orders and a menu) by simply updating a Google Sheet, making all of this far more accessible than most other options.

But first, some context.

Some context

In September 2017, as one of my first big passion projects at Distilled, I wrote a Moz blog post telling people how to make a chatbot and giving away some example code.

This April, I got an email from a man named Alexandre Silvestre. Alex had launched “a non-profit effort to help the local small business owners navigate these challenging times, save as many jobs as possible, and continue to serve our community while helping to flatten the curve.”

This effort began by focusing on restaurants. Alex had found my 2017 post (holy moly, content marketing works!) and asked if I could help his team build a chatbot. We agreed on some basic requirements for the bot:

- It had to work entirely within text message (and if the order was super complicated it had to be able to set up a call directly with the restaurant).

- Running it had to be as close to free as possible.

- Restaurants had to be able to check on orders, update menus, etc., without setting up special accounts.

The solution we agreed on had three parts:

- Twilio (paid): supplies the phone number and handles most of the conversational back-and-forth.

- Google Cloud Functions (semi-free): when a URL is called it runs code (including updating our database for the restaurant) and returns a response.

- Google Sheets (free): our database platform. We have a sheet which lists all of the businesses using our chatbot, and linking off to the individual Google Sheets for each business.

I’ll take you through each of these components in turn and tell you how to work with them.

If you’re coming back to this post, or just need help with one area, feel free to jump to the specific part you’re interested in:

—Pricing

—Twilio

—Google Sheets

—Google Cloud Functions

—Test the bot

—Break things and have fun

—Postscript — weird hacks

Pricing

This should all run pretty cheaply — I’m talking like four cents an order.

Even so, always make sure that any pricing alerts are coming through to an email address you actively monitor.

When you’re just starting on this, or when you’ve made a change (like adding new functionality or new businesses), make sure you check back in on your credits over the next few weeks so you know what’s going on.

Twilio

Local Twilio phone numbers cost about $1.00 per month. It’ll cost about $0.0075 to send and receive texts, and Twilio Studio — which we use to do a lot of the “conversation” — costs $0.01 every time it’s activated (the first 1,000 every month are free).

So, assuming you have 2,500 text orders a month and each order takes about five text messages, it’s coming to about $100 a month in total.

Google Sheets

Google Sheets is free, and great. Long live Google Sheets.

Google Cloud Functions

Google shares full pricing details here, but the important things to know about are:

1. Promotional credits

You get a free trial which lasts up to a year, and it includes $300 of promotional credits, so it’ll spend that before it spends your money. We’d spent $0.00 (including promotional credits) at the end of a month of testing. That’s because there’s also a monthly free allowance.

2. Free allowance and pricing structure

Even aside from the free credits, Google gives a free allowance every month. If we assume that each order requires about 5 activations of our code and our code takes up to five seconds to run each time (which is a while but sometimes Google Sheets is sluggish), we could be getting up to over 400,000 orders per month before we dip into the promotional credits.

Twilio

Twilio is a paid platform that lets you buy a phone number and have that number automatically send certain responses based on input.

If you don’t want to read more about Twilio and just want the free Twilio chatbot flow, here it is.

Step 1: Buy a Twilio phone number

Once you’ve bought a phone number, you can receive texts to that number and they’ll be processed in your Twilio account. You can also send texts from that number.

Step 2: Find your phone number

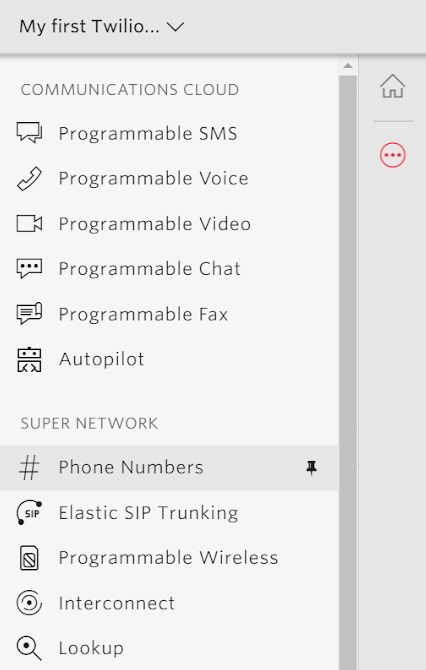

You can see your list of purchased phone numbers by clicking the Twilio menu in the top left hand corner and then clicking “Phone Numbers”. Or, you can just go to phone-numbers/incoming.

Once you see your phone number listed, make a note of it.

Step 3: Create your Studio Flow

Studio is Twilio’s drag-and-drop editor that lets you create the structure of your conversation. A studio “flow” is just the name of a specific conversation you’ve constructed.

You can get to Twilio Studio by clicking on the Twilio menu again and clicking on “Studio” under “Runtime”.

Create a new flow by clicking “Create a flow”.

When you create a new flow, you’ll be given the option to start from scratch or use one of the built-in options to build your flow for you (although they won’t be as in-depth as the template I’m sharing here).

If you want to use a version of the flow which Alex and I built, select “Import from JSON” and click “Next”. Then, download this file and copy the contents into the box that comes up.

Make sure that it starts with a single { brace, and ends with a single } brace. The box that comes up will automatically have {} in it and if you don’t delete them before you paste, you’ll double-up and it won’t accept your input.

If all goes well, you’ll be presented with a flow that looks like this:

You might be asking: What in the name of all that is holy is that tangle of colored spaghetti?

That’s the Twilio Studio flow we created and, don’t worry, it basically splits up into a series of multiple-choice questions where the answer to each determines where you go next in the flow.

Everything on the canvas that you can see is a widget from the Twilio Studio widget library connected together with “if this, then that” type conditions.

The Studio Flow process

Before we go into specific blocks in the process, here’s an overview of what happens:

- A customer messages one of our Twilio numbers

- Based on the specific number messaged, we look up the restaurant associated with it. We then use the name and saved menu of the restaurant to message the customer.

- If the customer tries to order off-menu, we connect a call to the restaurant

- If the customer chooses something from our menu, we ask their name, then record their order in the sheet for that restaurant and tell them when to arrive to pick up their order

- As/when the user messages to tell us they are outside the restaurant, we ask whether they are on-foot/a description of their vehicle. We record the vehicle description in the same restaurant sheet.

Let’s look at some example building blocks shall we?

Initial Trigger

The initial trigger appears right at the start of every flow, and splits the incoming contact based on whether it’s a text message, a phone call, or if code is accessing it.

“Incoming Message” means the contact was via text message. We only need to worry about that one for now, so let’s focus on the left-hand line.

Record the fact that we’re starting a new interaction

Next, we use a “Set Variables” block, which you can grab from the widget library.

The “Set Variables” block lets us save record information that we want to refer to later. For example, we start by just setting the “stage” of our interaction. We say that the stage is “start” as in, we are at the start of the interaction. Later on we’ll check what the value of stage is, both in Studio and in our external code, so that we know what to do, when.

Get our menu

We assume that if someone messaged us, triggering the chatbot, they are looking to order so the next stage is to work out what the applicable menu is.

Now, we could just write the menu out directly into Studio and say that whenever someone sends us a message, we respond with the same list of options. But that has a couple problems.

First, it would mean that if we want to set this up for multiple restaurants, we’d have to create a new flow for each.

The bigger issue is that restaurants often change their menus. If we want this to be something we can offer to lots of different restaurants, we don’t want to spend all our time manually updating Twilio every time a restaurant runs out of an ingredient.

So what we really need is for the restaurants to be able to list their own menus. This is where Google Sheets comes in, but we’ll get to that later. In Twilio, we just need to be able to ask for external information and forward that external information to the user. To do that we use a Webhook widget:

This widget makes a request to a URL, gets the response, and then lets us use the content of the response in our messages and flow.

If the request to the URL is successful, Twilio will automatically continue to our success step, otherwise we can set it to send an “Oops, something went wrong” response with the Fail option.

In this case, our Webhook will make a request to the Google Cloud functions URL (more on that later). The request we send will include some information about the user and what we need the code to do. The information will be in JSON format (the same format that we used to import the Twilio flow I shared above).

Our JSON will include the specific Twilio phone number that’s been messaged, and we’ll use that number to differentiate between restaurants, as well as the phone number that contacted us. It’ll also include the content of the text message we received and the “stage” we set earlier, so the code knows what the user is looking for.

Then the code will do some stuff (we’ll get to that later) and return information of its own. We can then tell Twilio to use parts of the response in messages.

Send a message in response

Next we can use the information we received to construct and send a message to the user. Twilio will remember the number you’re in a conversation with and it’ll send your messages to that number.

This is the “Send & Wait For Reply” widget, meaning that once this message is sent, Twilio will assume the conversation is still going rather than ending it there.

In this case, we’re writing our welcome message. We could write out just plain content, but we want to use some of the variables we got from our Webhook widget. We called that specific Webhook widget “get_options”, so we access the content we got from it by writing:

{{widgets.get_options

The response comes back in JSON, and fortunately Twilio automatically breaks that up for us.

We can access individual parts of the response by writing “parsed” and then the label we gave that information in our response. As it is, the response from the code looked something like this:

{“name”: restaurant_name,

“dishes_string”: “You can choose from Margherita Pizza, Hawaiian Pizza, Vegetarian Pizza”

“additions”: “large, medium, small”}

We get the available menu by writing “{{widgets.get_options.parsed.dishes_string}}”, and then we write the message below which will be sent to people who contact the bot:

Make a decision based on a message

We can’t assume everyone is going to use the bot in exactly the same way so we need to be able to change what we do based on certain conditions. The “Split Based On…” widget is how we select certain conditions and set what to do if they are met.

In this case, we use the content of the response to our previous message which we access using {{options_follow_up.inbound.Body}}. “Options_follow_up” is the name of the Send & Wait widget we just spoke about, “inbound” means the response and, “Body” means the text within it.

Then we set a condition. If the user responds with anything along the lines of “other”, “no”, “help”, etc., they’ll get sent off on another track to have a phone call. If they respond with anything not on that list, they might be trying to order, so we take their order and check it with our code:

Set up a call

If the user says they want something off-menu, we’ll need to set up a call with the restaurant. We do that by first calling the user:

Then, when they pick up, connecting that call to the restaurant number which we’ve already looked up in our sheets:

Step 4: Select your studio flow for this phone number

Follow the instructions in step two to get back to the specific listing for the phone number you bought. Then scroll to the bottom and select the Studio Flow you created.

Google Sheets

This chatbot uses two Google Sheets.

Free lookup sheet

The lookup sheet holds a list of Twilio phone numbers, the restaurant they have been assigned to, and the URL of the Google Sheet which holds the details for that restaurant, so that we know where to look for each.

You’ll need to create a copy of the sheet to use it. I’ve included a row in the sheet I shared, explaining each of the columns. Feel free to delete that when you know what you’re doing.

Free example restaurant sheet

The restaurant-specific sheet is where we include all of our information about the restaurant in a series of tabs. You’ll need to create a copy of the sheet to use it.

Orders

The orders tab is mainly used by our code. It will automatically write in the order time, customer name, customer phone number, and details of the order. By default it’ll write FALSE in the “PAID/READY?” column, which the restaurant will then need to update.

In the final stage, the script will add TRUE to the “CUSTOMER HERE?” column and give the car description in the “PICK UP INFO” column.

Wait time

This is a fairly simple tab, as it contains one cell where the restaurant writes in how long it’ll be before orders are ready. Our code will extract that and give it to Twilio to let customers know how long they’ll likely be waiting.

Available dishes and additions tabs

The restaurant lists the dishes that are available now along with simple adaptations to those dishes, then these menus are sent to customers when they contact the restaurant. When the code receives an order, it’ll also check that order against the list of dishes it sent to see if the customer is selecting one of the choices.

Script using sheet tab

You don’t need to touch this one at all — it’s just a precaution to avoid our code accidentally overwriting itself.

Imagine a situation where our code gets an order, finds the first empty row in the orders sheet, and writes that order down there. However, at the same time, someone else makes an order for the same restaurant, another instance of our code also looks for the first empty row, selects the same one, and they both write in it at the same time. We’d lose at least one order even though the code thinks everything is fine.

To try to avoid that, when our code starts to use the sheet, the first thing it does is change the “Script using sheet” value to TRUE and writes down when it starts using it. Then, when it’s done, it changes the value back to FALSE.

If our script goes to use the sheet and sees that “Script using sheet” is set to TRUE, it’ll wait until that value becomes FALSE and then write down the order.

How do I use the sheets?

Example restaurant sheet:

- Make a copy of the example restaurant sheet.

- Fill out all the details for your test restaurant.

- Copy the URL of the sheet.

Lookup sheet:

- Make a copy of the lookup sheet (you’ll only need to create one).

- Don’t delete anything in the “extracted id” column but replace everything else.

- Put your Twilio number in the first column.

- Paste the URL of your test restaurant in the Business Sheet URL column.

- Add your business’ phone number in the final column.

Sharing:

- Find the “Service Account” email address (which I’ll direct you to in the Cloud Functions section).

- Make sure that both sheets are shared with that email address having edit access.

Creating a new restaurant:

- Any time you need to create a new restaurant, just make a copy of the restaurant sheet.

- Make sure you tick “share with the same people” when you’re copying it.

- Clear out the current details.

- Paste the new Google Sheet URL in a new line of your lookup sheet.

When the code runs, it’ll open up the lookup sheet, use the Twilio phone number to find the specific sheet ID for that restaurant, go to that sheet, and return the menu.

Google Cloud Functions

Google Cloud Functions is a simple way to automatically run code online without having to set up servers or install a whole bunch of special programs somewhere to make sure your code is transferable.

If you don’t want to learn more about Google Cloud and just want code to run — here’s the free chatbot Python code.

What is the code doing?

Our code doesn’t try to handle any of the actual conversations, it just gets requests from Twilio — including details about the user and what stage they are at — and performs some simple functions.

Stage 1: “Start”

The code receives a message from Twilio including the Twilio number that was activated and the stage the user is at (start). Based on it being the “start” stage, the code activates the start function.

It looks up the specific restaurant sheet based on the Twilio number, then returns the menu for that restaurant.

It also sends Twilio things like the specific restaurant’s number and a condensed version of the menu and additions for us to check orders against.

Stage 2: “Chosen”

The code receives the stage the user is at (chosen) as well as their order message, the sheet ID for the restaurant, and the condensed menu (which it sent to Twilio before), so we don’t have to look those things up again.

Based on it being the “chosen” stage, the code activates the chosen function. It checks if the order matches our condensed menu. If they didn’t, it tells Twilio that the message doesn’t look like an order.

If the order does match our menu, it writes the order down in the first blank line. It also creates an order ID, which is a combination of the time and a portion of the user’s phone number.

It sends Twilio a message back saying if the order matched our menu and, if it did match our menu, what the order number is.

Stage 3: “Arrived”

The code receives the stage the user is at (arrived) and activates the arrived function. It also receives the message describing the user’s vehicle, the restaurant-specific sheet ID, and the order number, all of which it previously told Twilio.

It looks up the restaurant sheet, and finds the order ID that matches the one it was sent, then updates that row to show the user has arrived and the description of their car.

Twilio handles all the context

It might seem weird to you that every time the code finds some information (for instance, the sheet ID to look up) it sends that information to Twilio and requests it afresh later on. That’s because our code doesn’t know what’s going on at all, except for what Twilio tells it. Every time we activate our code, it starts exactly the same way so it has no way of knowing which user is texting Twilio, what stage they’re at, or even what restaurant we’re talking about.

Twilio remembers these things for the course of the interaction, so we use it to handle all of that stuff. Our code is a very simple “do-er” — it doesn’t “know” anything for more than about five seconds at a time.

How do I set up the code?

I don’t have time to describe how to use Google Cloud Functions in-depth, or how to code in Python, but the code I’ve shared above includes a fair number of notes explaining what’s going on, and I’ll talk you through the steps specific to this process.

Step 1: Set up

Make sure you:

Step 2: Create a new function

Go here and click “create a new function”. If you haven’t created a project before, you might need to do that first, and you can give the project whatever name you like.

Step 3: Set out the details for your function

The screen shot below gives you a lot of the details you need. I’d recommend you choose 256MB for memory — it should be enough. If you find you run into problems (or if you want to be more cautious from the start), then increase it to 512MB.

Make sure you select HTTP as the trigger and note down the URL it gives you (if you forget, you can always find the URL by going to the “Trigger” tab of the function).

Also make sure you tick the option to allow Unauthenticated Access (that way Twilio will be able to start the function).

Select “Inline editor” and paste in the Gist code I gave you (it’s heavily commented, I recommend giving it a read to make sure you’re happy with what it’s doing).

Click “REQUIREMENTS.TXT” and paste in the following lines of libraries you’ll need to use:

- flask

- twilio

- pytz

Make sure “function to execute” is SMS, then click the “Environment Variables” dropdown.

Just like I’ve done above, click “+ ADD VARIABLE”, write “spreadsheet_id” in the “Name” column, and in the “Value” column, paste in the ID of your lookup sheet. You get the ID by looking at the URL of the lookup sheet, and copying everything between the last two slashes (outlined in red below).

Click on the “Service account” drop down. It should come up with just “App Engine default service account” and give you an email address (as below) — that’s the email address you need all of your Google Sheets to be shared with. Write it down somewhere and add it as an edit user for both your lookup and restaurant-specific sheets.

Once you’ve done all of that, click “Deploy”.

Once you deploy, you should land back on the main screen for your Cloud Function. The green tick in the top left hand corner tells you everything is working.

Step 4: Turn on Sheets API

The first time your code tries to access Google Sheets, it might not be able to because you need to switch on the Google Sheets API for your account. Go here, select the project you’re working on with the dropdown menu in the top left corner, then click the big blue “ENABLE” button.

Step 5: Go back to Twilio and paste in the HTTP trigger for your code

Remember the trigger URL we noted down from when we were creating our function? Go back to your Twilio Studio and find all of the blocks with the sign in the top left corner:

Click on each in turn and paste your Google Cloud URL into the REQUEST URL box that comes up on the right side of the screen:

Test the bot

By now you should have your Cloud Function set up. You should also have both of your Google Sheets set up and shared with your Cloud Function service account.

The next step is to test the bot. Start by texting your Twilio number the word “order” to get it going. It should respond with a menu that your code pulls from your restaurant-specific Google Sheet. Follow the steps it sends you through to the end and check your Google Sheet to make sure it’s updating properly.

If for some reason it’s not working, there are two places you can check. Twilio keeps a log of all the errors it sees which you can find by clicking the little “Debugger” symbol in the top right corner:

Google also keeps a record of everything that happens with your Cloud Function. This includes non-error notifications. You can see all of that by clicking “VIEW LOGS” at the top:

Conclusion: break things and have fun

All of this is by no means perfect, and I’m sure there’s stuff you could add and improve, but this is a way of building a network of scalable chatbots, each specific to a different business, and each partially managed by that business at minimal cost.

Give this a try, break it, improve it, tear it up and start again, and let me know what you think!

Postscript: weird hacks

This bit is only really for people who are interested, but because we’ve deliberately done this on a shoestring, we run into a couple weird issues — mainly around requests to our bot when it hasn’t been activated for a bit.

When Twilio gets messages for the first time in a while, it turns on pretty quickly and expects other things to do so, too. For example, when Twilio makes requests to our code, it assumes that the code failed if it takes more than about five seconds. That’s not that unusual — a lot of chat platforms demand a five-second max turnaround time.

Cloud Functions are able to run pretty fast, even with lower memory allowances, but Google Sheets always seems to be a bit slow when accessed through the API. In fact, Google Sheets is particularly slow if it hasn’t been accessed in some time.

That can mean that, if no one has used your bot recently, Google Sheets API takes too long to respond the first time and Twilio gives up before our code can return, causing an error.

There are a couple parts of our script designed to avoid that.

Trying again

The first time we activate our Cloud Function, we don’t want it to actually change anything, we just want information. So in Twilio, we start by creating a variable called “retries” and setting the value as 0.

If the request fails, we check if the retries value is 0. If it is, then we set the retries value to 1 and try again. If it fails a second time, we don’t want to keep doing this forever so we send an error and stop there.

Waking the sheet up

The second time we activate our Cloud Function we do want it to do something. We can’t just do it again if it doesn’t return in time because we’ll end up with duplicate orders, which is a headache for the restaurant.

Instead, during an earlier part of the exchange, we make a pointless change to one of our sheets, just so that it’s ready for when we make the important change.

In our conversational flow we:

- Send the menu

- Get the response

- Ask for the user’s name

- Write the order

We don’t need to do anything to the sheet until step four, but after we get the user’s response (before we ask their name), we activate our code once to write something useless into the order sheet. We say to Twilio — whether that succeeds or fails — keep going with the interaction, because it doesn’t matter at that point whether we’ve returned in time. Then, hopefully, by the time we go to write in our order, Google Sheets is ready for some actual use.

There are limitations

Google Sheets is not the ideal database — it’s slow and could mean we miss the timeouts for Twilio. But these couple of extra steps help us work around some of those limitations.